Q&A with Trans Pride Initiative

Nell Gaither, President of TPI , on supporting trans people in Texas prisons.

It’s been two weeks since I last sent a newsletter. While Queer Tejas is a project that excites and motivates me, the reality is that this newsletter takes substantial time and effort to put together. I had a couple of deadlines come up within the last two weeks that became a priority for me since it’s paid work so the newsletter had to be put on the back burner for a bit. I should probably rethink the frequency of this newsletter, but for now, I’m going to stick to a weekly schedule! I’ve got ~content~ planned for the rest of the year so, onward! Thank you for joining me while I experiment with this newsletter medium. Please share and subscribe. 🌈

Queer and trans people have long been at the forefront of protesting the police. Just in case you forgot or didn’t know, Pride celebrations commemorate the anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, when queer and trans people fought back against the police at Stonewall Inn in June 1969. During the time, police surveilled and targeted queer and trans people at gay bars across the country. Although homophobic laws have changed, queer and trans people continue to suffer from police violence and violence in prisons today.

Dean Spade, trans activist and lawyer, writes about why abolition is important to queer and trans resistance and why it’s key to our liberation:

“Queer and trans liberation is inextricable from other leftist liberation movements — feminism, migrant justice, Black liberation, disability justice, and more. All marginalized and targeted groups face not only poverty and housing insecurity, but also police violence and targeted criminalization and deportation. All these movements imagine another world where all people have what they need, no one is exploited to enrich others, and we don’t live with a violent standing army of police endangering our lives and using resources that could be better put toward housing, health care, and childcare.”

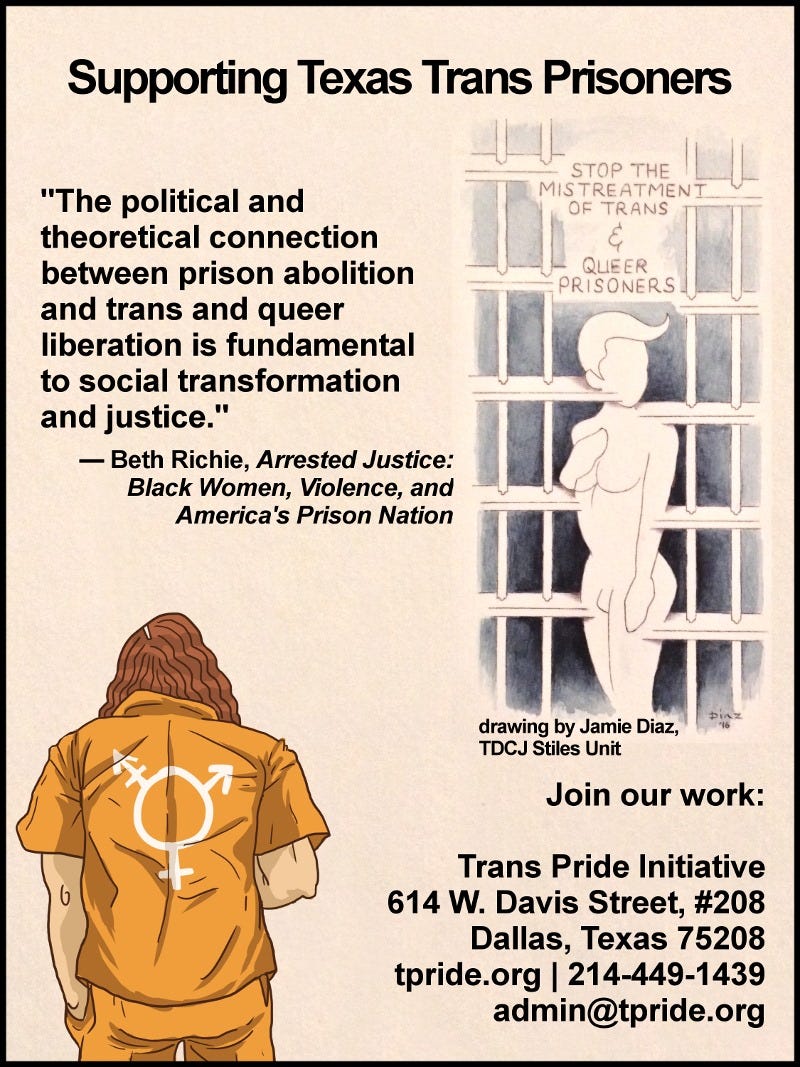

With the many ongoing conversations about abolition and defunding the police, I thought it would be a great time to talk to Trans Pride Initiative, a Dallas-based organization that advocates for trans and queer people in the Texas prison system, as well as in the areas of housing, healthcare, and employment.

I spoke to Nell Gaither, President of TPI, to learn more about what TPI is all about. We spoke about TPI’s letter writing program, human rights violations in Texas prisons, and why abolition is necessary. Follow TPI on Instagram and Twitter or subscribe to their newsletter for regular updates.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Yvonne: Can you start off and tell me a little bit about yourself and what you do at Trans Pride Initiative?

Nell Gaither, President of TPI: Well, I'm white, pansexual, queer, trans femme. I use she/her or they/them pronouns. I've been involved in Trans Pride since we began back in 2011.

How did you become involved with TPI?

I helped start it.

Our mission was to advocate and support trans and gender diverse persons in areas of housing, health care, education, and employment. We started off working in health care, and trying to expand access to health care services for trans persons, as well as housing. At that time, back in 2011, for example, the city of Dallas — I was working for the city of Dallas — did not have any trans coverage for their employees. We started working with that and shelters. We volunteered at shelters to try to expand access to trans services and improve policies. Back in the beginning, we focused mainly on access to more equitable housing, especially for low-income and indigent persons, as well as better access to health care from insurance policies to public employers, like the city of Dallas, rather than private employers, to improve their coverage of trans care. And basically doing whatever we could to get involved in figuring out ways to expand access in various ways.

So how did TPI’s work expand to support prisoners?

In 2013, we were starting to get interested in anti-violence work. A lot of times anti-violence work has to do with sexual assault. And so certainly our definition of anti-violence includes sexual assault, but we see things like disrespect for persons in not allowing bathroom access, refusing pronouns, and refusing identification documents — we see that as anti-violence work as well.

Around 2013, we got a letter from somebody in a Texas prison that said she had been trying to get — she is a trans woman — to get access to hormones. She had not been on hormones in the free world. She didn't know what trans was in the free world. She'd been, at that time, around 18 years, I believe. She discovered what being trans was while she was inside through working with a counselor. There's very few supportive counselors in the Texas prison system, but she found one that was, or got lucky and had one that was, and so she was trying to start hormones and they would not let her. So she wrote to us asking if we could help her.

We reached out to several different organizations that either did prison work or knew more about prison work and advocating in the prison system, and nobody would help us. Lambda Legal actually wrote back and said, they would not help any trans person accessing health care in Texas, in the prison system. And that really, personally, made me mad. And so I said, okay, we're going to help her and four months later, she was on hormones. I don't think that was due to us, I think that was just happening to be at the right place at the right time. But it was nice to have what felt like a success. Anyway, now that I know the prison system better, I know that we weren't the single cause of that. She started hormones, and she started spreading word about us in the system and that just gradually became a much bigger part of what we do.

We would like to still be doing things like health care and housing, as well as education and employment issues, but we also see that there's so few people doing this type of prison support work that it's really needed. We feel like we fulfill a necessary aspect of doing anti-violence and trans support work in that.

I should say that we don't just support trans persons in the prison system; we have straight people writing to us, we have queer persons, we have gay persons. We don't say that we won't help somebody who's not trans or not gender diverse. We see ourselves as both a trans organization that's helping trans persons but also showing that trans persons can do the work to help everybody.

About how many trans people are in the TDCJ (Texas Department of Criminal Justice) system?

It's hard to tell officially. There's two different levels of trans identity in the TDCJ system. One is called the TRGN marker, which is the official designator in their file that says you're either trans or intersex. So the TRGN marker says either one of those. We work with people who are intersex, who write to us also.

The official count is somewhere over 1,200 now. When we first started doing this, it was about 30, so it's grown from 30 out of 150,000 to 1,200 out of about 125,000 now.

In 2012, TDCJ was prescribing hormones to folks, but they had to meet really strict requirements. It was pretty rare for somebody to meet those requirements. The person who is in charge of that program was very narrow minded. He's actually involved in trans health care, and is oftentimes thought as a supporter of trans health care, but he's very narrow in the terms of what he considers a trans person. He told me at one point that there should only be two trans persons in a population of 150,000. He's using that old definition of what a “true transexual” is or what we sometimes call truscum.

At that point, based on population estimates and disproportional arrest and incarceration of persons who are gender non-conforming, I estimated there should be between 1,000 and 1,500 persons in TDCJ. Now we're seeing that number of over 1,200 persons identified.

But we also know that some people are identifying — because identifying as trans with just the TRGN marker sometimes gets, at least what people think are, benefits such as a single cell, sometimes safer housing, sometimes it's not safer, but some people think it is. So we know some people are identifying just for other reasons. But we also know that some people are not identifying, because they're afraid of the endangerment that identifying as trans does. I think somewhere around 1,200 is probably a realistic figure, although the individuals that are identified, maybe not an accurate reflection of each individual.

The other characteristic of identifying as trans in the system is being on hormones. We don't believe that somebody identifying as trans has to undergo medical intervention; that should not be a requirement. But there are people in the system who are just identifying as the TRGN marker, but never seek hormones. So we don't know how many are seeking hormones, or how many persons who are identifying as TRGN but not seeking hormones might be doing so for other purposes, not because they identify as trans. There's kind of a gray area, that's a little bit difficult, because my feeling is, most people are not going to identify as trans in the prison system just for those kind of manipulation reasons because there's too much endangerment involved. But other people say no, they know people inside who are doing that, and who admit they're doing that. And I sometimes wonder, well, you may not be getting the whole truth from that person. But it's an area that's kind of hard to tell on that.

In TPI'S newsletters, it says there's a need for more volunteers for prison support efforts. Can you tell me a little bit about the letter writing program and what volunteers do?

We've moved online since April of last year. We basically have a spreadsheet that currently has a little under 200 persons on it and these are persons who are waiting for a letter, some may have written more than one time. Some have just written once, and they're waiting for a letter. But each row is a person waiting on a response from us and right now we're a little bit over two months behind in responses.

What somebody does is they go to the spreadsheet, and they can click on a link that, if they have a password and username, takes them into the more secure area site and they can go look at that person's letters and see if they feel comfortable responding to that person. If they do, then, if it's a new person, they download a template. The template gives them some basic information about what we do, what we can do in supporting them, what kind of information we collect for documenting violence in the system and other basic information like that, and then they respond to their letters. They've got that template they can work with to give them basic assistance in writing a letter.

If it's an existing person who we've exchanged letters with, there's no template, they just answer the letter. And then that's uploaded to the server, and they notify me that they're done. And I mail it out, so they don't have to pay for anything. We cover postage and all materials and things like that.

How is it communicated that you're doing this letter writing program to people in prison?

Word of mouth. We haven't advertised, but other places have learned about us and they sometimes put us in their resource directories. In 2015, somebody wrote a letter to Black and Pink and they ran it in their newsletter. This was somebody we've been writing to, and they wanted to mention us, saying, hey, if you're trans, and you need help, or you want somebody to write to, write to TPI. That was something that increased knowledge about us. Just Detention International and Inside Books Project — I believe we're in their resource directories. We don't know what resource directories were in. So that's a way that word gets out. But mostly, it's just word of mouth. In fact, most letters we get will say, so and so told me that y'all might be able to help with the situation or something like that.

And usually, are people writing for help? Or is it more like they’re looking for pen pals or something like that?

Well, our program is a little bit different than most pen pal programs, because we don't really consider ourselves being pen pals. But we're not exactly not pen pals. We respond to every letter. So if somebody writes in, says, hey, just touching base with y'all, just wanted to let you know this is going on in my life. We write them back and it's a friendly letter. Some people write personal things about what's going on in their lives and things that are pen pal-like. But the majority of our letters are dealing with issues from assault, sexual assault, suicide. We've had reports of people murdered. Most of the things that we deal with are a little bit more advocacy-related or documenting violence. We had a volunteer out in California this past year and they were writing pen pals with Black and Pink and they said the type of letters we write are much different from what they would see with Black and Pink, which are more pen pal, friendly letters.

TPI along with the Human Rights Clinic and the Austin Community Law Center recently released a report called Naming and Shaming, on human rights violations experienced by trans people in prison. What were some main findings from the report?

Attorneys that we're working with have sued the state of Texas and that's called our Project 103, named after Texas Family Code 45.103, which excludes persons from being able to change their name — and in Texas, that means gender markers as well — if they have a felony conviction for at least two years after completing all terms of their sentence.

So the report found there's a lot of different levels of violence against persons in the prison system in TDCJ and that that violence is compounded by the disrespect that goes along with failure to recognize one's identity. Name is a very important part of that identity. And that translates into increased violence in the system, as well as things like violence in the state system in the sense that the state requires trans persons to pay for background checks, in order to change your name, but that's a state function. I thought that was a really important thing to bring out in that report, that it's actually a state function to perform background checks, but they're requiring us to take care of that for changing our name.

And so it found that these various things impact trans health and safety, and that these are also in violation of international human rights law that the United States claims to comply with. There's actually another step to that that's going on now that I can't talk about, but that work is still going on with the Human Rights Clinic.

There's been a lot more conversations about abolition in the national spotlight right now. TPI mentions abolition work in the newsletters, so what are some ways people can have a deeper understanding of abolition?

I think that there are much more competent speakers than I am on abolition in general like Angela Davis and Mariame Kabe and some of the people that are doing some current writing and teaching in abolition and transformative justice.

I think what is really important at this stage is to be attuned to those conversations that are going on and be open to understanding what abolition actually is, and how it's tied to perspectives and transformative justice. I think a lot of people don't understand how abolition is a long-term perspective and that the ways we deal with social harm, in terms of retributive justice models, just doesn't work. It actually creates more harm and does nothing to achieve the stated goals of a justice system. It's simply getting revenge, basically, and making money.

I think one of the things that is really important is for people to be open to those conversations that are going on now because there's a lot of misunderstanding of what the abolition movement is and what retributive justice means and what transformative justice means.

So in your opinion, as a trans person and someone who's doing this work, why do you think abolition is necessary?

The prison system, as it exists today, is violence. Violence for the sake of profiteering. The system that we have now privileges the top of the pyramid: cis, straight, white males, and penalizes everyone else. And that penalty or lack of privilege or discrimination compounds as you extend multiple layers of marginalization. And the driver of that is power and money.

TDCJ is the largest, I believe this is still true, is the largest agency in Texas in the entire state. It's the most powerful government agency in Texas and there's a huge amount of money. Even though you can claim that, well, TDCJ is a public agency. Still, there's so many funds tied into the different aspects of prison, from the manufacturing that uses prison labor for various things to Securus, the telephone system and communications, to monitors and fees.

I think there's another issue that as a trans person — and this would go for anybody who experiences some degree of marginalization, so it's racial marginalization, it's education marginalization, it's mental health marginalization…So many times our advocacy efforts help the people that are easy to help. That only helps those people who already have substantial privilege. But when you start looking at making changes to address the inequities within the systems of privilege, you start addressing people who don't fit those perfect little niches at the top — that helps everybody.